Prom season

GCSEs are finally done, and around the country, we're gearing up for Prom season. Some people find it uncomfortable -but I think it's kind of amazing.

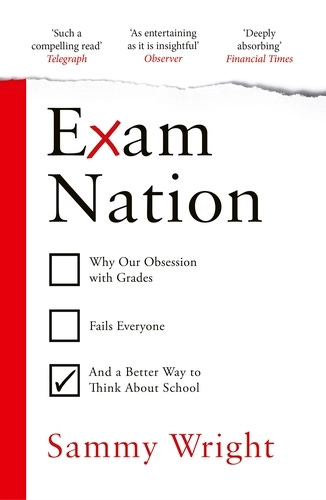

This is an extract from my book, Exam Nation, available in hardback and out in paperback this Autumn. This particular section comes from a chapter called Community. I love it - not because I can claim any great genius - but as a reminder of when I wrote it, the day after year 11 Prom.

On another hot and muggy July night, two weeks after my visit to London, I am back in Sunderland and make my way slightly reluctantly up the back stairs of a local sea-front hotel. In the bar I scan for familiar faces and see, with a jolt of unfamiliarity, a group of figures in evening dress. They are colleagues and, not for the first time, I feel underdressed. Round here, people take their nights out seriously – and at Year 11 Prom, it’s not only the kids who want to make an impression. I, on the other hand, have a tendency to think a checked shirt is the height of smart-casual sophistication.

Prom gets a bad press. Creeping Americanisation, apparently. A parade of grim flouncy dresses and spray tans. The commercialisation of childhood carried to a glittery extreme. And there is plenty that night to fuel that narrative. Some children are dropped off by their parents. Some come in specially hired cars. I see a Mustang, a limo and a gleaming black Rolls-Royce. One pair even arrives in a horse-drawn carriage, complete with feathery plumes and a top-hatted driver. As they step out of their vehicles, there is the unmistakeable feeling of an ersatz red-carpet event, with dresses that generally adhere to the maxim ‘the bigger, the better’ – sequins, tulle, glittering headpieces, corsets – and suits that lean towards the brash, with loud checks and gold chains and white waistcoats much in evidence. Phones are out, selfie follows selfie and an appreciative audience gathers.

I look at that audience. Nans, dads, mams (not mums – this is the North-East) and a host of younger kids all watch the parade, ranging from giddy to teary. Sometimes their elder siblings turn up, too, kids I taught a few years back, now at uni or working, sometimes with children themselves. They come over to say hi, to say thanks again.

The leavers keep on coming. They step out of their vehicles perfectly poised on the cusp of adulthood, made up into what they imagine grown-ups to be. Their eyes dart sideways, their faces both embarrassed and euphoric. The girls teeter on their heels, in the folds of their wedding-cake dresses, and shriek delightedly at themselves and their friends, while the boys slowly warm up, from hands on shoulders into awkward and then heartfelt hugs.

I stand at the back of the throng and talk to two girls, best friends, who for five years have giggled their way around the school in a strange little bubble of innocence. All the things there might be in their lives that are sad and troubling – and there are many – can be forgotten for a moment as they stand, gobsmacked at themselves in matching purple dresses, their make-up applied with the aid of a member of staff in a room booked by the school specially for them at the hotel.

Teacher after teacher approaches and speaks to them. When we catch each other’s eyes there is a jolt of pure emotion, a heart-wrenching wonder at the ways childhood can be so hard and so magical. Later in the evening, one of these two girls will be so overwhelmed that she starts hyperventilating. We’ll take her out to the front again, empty now, her friend as ever by her side, and practise breathing. Another member of staff will stop and talk to the two of them gently, joking with them in the softest, kindest way.

But right now, up front, more and more students arrive.

For each of these children, stepping out of their shiny cars, I remember the difficulties, the moments of panic and anger. And yet here they are. Prom is just a symbol, but symbols have power, and in this moment they do seem like they have changed, and grown.

Forty-nine teachers are here tonight, most of them voluntarily, paying for their own tickets, wanting to participate in the celebration with the kids. We play bingo together, count down to confetti cannons, then all dance in a hectic mass, bouncing first to generic hits and then, as the evening progresses, they bring out the big guns. Every prom or school party I’ve been to in Sunderland has played these: ‘Cha Cha Slide’, ‘Macarena’ and a weird, happy hardcore song called ‘Children of the Night’.

And everyone dances. Teachers, students, boys, girls. Boys dressed as girls, and girls dressed as boys – because, every year, the flounces and frills are only part of the story. Girls in suits and a tall, strikingly made-up boy in a backless blue gown mingle, with no comment at all from the other students. A colleague grabs me and makes me spin her, to cheers from the kids and the teachers. Another colleague – the head of Maths – bounces with a glowstick in each hand like he’s in a field in 1990, despite having turned up in full tuxedo and shiny shoes.

Throughout the night, kids grab teachers and ask for photos with them. Two students of mine give me an Avengers tie. A group of boys dance for the whole time, sweatily holding each other’s hands and hugging.

At the end I stand with a couple of other teachers at the door as the kids drift out into the night. They say ‘bye’ and ‘thank you’ as they go. We remind every single girl to lift up her train, so it doesn’t get wet on the steps – some of the boys do it for them. Many of them wear the flip-flops we provided for when the unfamiliar heels get too much. From the door I watch a group of boys at the bus stop opposite waiting for the night-bus. Every now and then they duck behind the sea wall, presumably to drink from illicit supplies. There will be parties and after-parties. People will be sick.

As the two friends leave, I ask if they had fun.

‘It was difficult,’ says the one who had been hyperventilating. She has the serious, unquestioning honesty of a five-year-old. ‘But it was great.’

In this book I sometimes try to use the proper terminology and call them pupils or students. But most of the time I find myself reverting to ‘kids’. Because that is how I see them. They are children, and they live with us in our school for half of their waking lives. It’s easy to criticise things like proms from the outside – but when it’s your kids, your pupils, you don’t see that. You see simply the sheer exhilaration of being sixteen and having your whole life ahead of you.

Ignore the flounces and the frills. Most important of all is that an event like this is safe, and warm. Like a first trip abroad with your class. Like the day at the end of term when the teacher brings in cake. Like all the ways in which schools are not simply factories, they are also homes. And celebrating this in a way that makes strong, positive, hopeful memories – sometimes for kids who don’t have many of these – is far from the least that schools do.